Difference between revisions of "Rainwater harvesting"

Jenny Hill (talk | contribs) (Created page with "This article is about large, integrated rainwater harvesting systems. For smaller, seasonal, outdoor, residential systems, see Rain Barrels <div class="col-md-8">{{TOCli...") |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 16:58, 1 August 2017

This article is about large, integrated rainwater harvesting systems. For smaller, seasonal, outdoor, residential systems, see Rain Barrels

Overview[edit]

Rainwater harvesting (RWH) is the ancient practice of collecting and storing precipitation for later use. Although Ontario is a region with relatively abundant fresh water, RWH is increasing in popularity for a number of reasons:

- The simplicity of selecting and installing a system, owing to improvements in the technology and the development of a local industry,

- The ease of modelling RWH in a stormwater management (SWM) plan, owing to the fixed size of the catchment and the cistern,

- Increasing transparency of storm sewer costs in some municipalities, and

- Increasing utility rates for potable water supply.

Rainwater harvesting is an ideal technology for:

- Sites which cannot infiltrate water owing to contaminated soils or shallow bedrock,

- Zero-lot-line developments such as condos or dense urban infill, or conversely

- Projects with extensive gardens and landscapes which would benefit from free irrigation water.

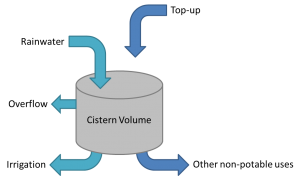

The fundamental components of a rainwater harvesting system are:

- the catchment area where the rain lands (e.g. rooftop),

- a screen or filter to remove coarse debris (mostly leaves),

- a cistern which will store the collected rainwater and preserve its quality,

- the connecting pipe network including roof drains.

Additional components may include:

- pumps to lift water to higher elevations, depending on the layout of the components,

- additional water filtration and treatment, depending on the intended use of the water.

<panelSuccess>

</panelSuccess>

Planning Considerations[edit]

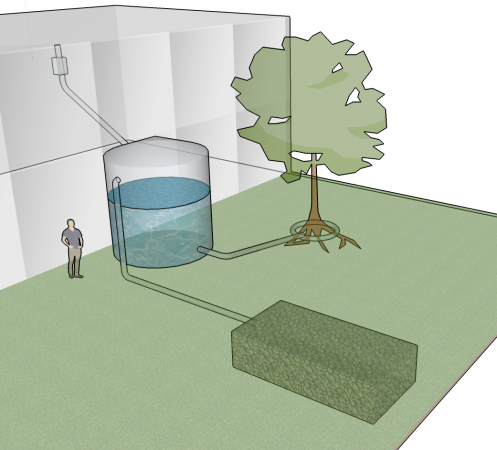

Place in the Treatment Train

To maximize the volume of water available for reuse, a RWH system is usually located near to the front of a treatment train. i.e. Upstream of other LID technologies. The most common exception would be where a site strategy employs a green roof. A simple warm-weather system may capture all of the rooftop runoff in an external tank above grade and use it for sub-surface irrigation. In this scenario the tank can overflow via gravity to a sub-surface infiltration chamber or a bioretention cell. But, if the tank is located below the ground or inside a building the overflow may need a pump.

Catchments

The origin of the harvested water affects the permissible end uses. Some of the most common uses include irrigation and flushing or toilets and urinals. As mixed source water can only be applied to the more limited end uses, selecting the catchments for a RWH system requires careful consideration.

- The Ontario Building Code (OBC) regulates the use of harvested rainwater as one of many non-potable water sources. "Rainwater means storm sewage runoff that is collected from a roof or the ground, but not from accessible patios and driveways."

- The CSA standard separates "roof runoff" from all other sources, including landscaped areas and green roofs. Collectively the green roof/landscaped and paved areas result in "stormwater runoff."

The current disparity between these two definitions affects all vegetated landscapes including green roofs. Confusion over terminology and regulation has been identified as a significant barrier to implementation of RWH since 2010[1].

Cistern and Pipework

Cisterns must be installed in locations where native soils or the building structure can support the load associated with the volume of stored water.

Expansion caused by freezing water will damage pipes, pumps and the cistern. There are two options for managing a RWH system in our climate:

- The entire system is drained and closed off ahead of sub-zero temperatures

- All pipework, pumps, filters and the cistern are protected from freezing during the winter

The first option may be suitable for systems optimized for exterior irrigation only. But regulatory authorities may not permit the use of such seasonal systems as part of a storm water control strategy. Year round systems can be protected from freezing by locating the pipes, pumps and cistern indoors and/or below the frost penetration depth[2].

Design for Maintenance

Detailed inspection and maintenance advice can be found in Sustainable Technologies' LID I&M guide.

The two primary operational concerns for RWH systems are:

- A leak developing,

- Debris obstructing some part of the plumbing.

Planning can help ensure that these are identified and fixed more easily and cheaply. Example questions:

- Is the roof (catchment) readily accessible to sweep debris periodically?

- Could the accumulation of debris on the roof be reduced by removing any overhanging branches?

- Can the leaf screens accessed from the roof? Or from a maintenance room?

- Will the cistern require entry for inspection in the future? How will this be accessed?

RWH systems producing higher quality water will have additional maintenance requirements. These will depend on the the treatment technologies being used.

<panelSuccess>

</panelSuccess>

Design[edit]

<h4blue>Sizing & modeling</h4blue>

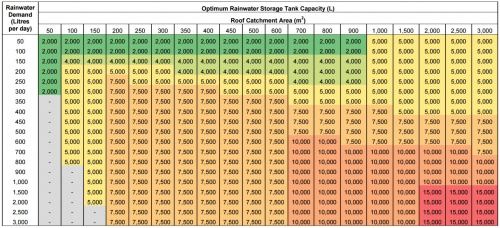

Simple[edit]

The following approximations Five percent of the average annual yield can be estimated:

Where:

- Y0.05 is five percent of the average annual yield (L)

- Ac is the catchment area (m2)

- Cvol, A is the annual runoff coefficient for the catchment

- Ra is the average annual rainfall depth (mm)

- e is the efficiency of the pre-storage filter

- Filter efficiency (e) can be reasonably estimated as 0.9 pending manufacturer’s information.

- In a study of three sites in Ontario, STEP found the annual Cvol, A of the rooftops to be around 0.8 [3]. This figure includes losses to evaporation, snow being blown off the roof, and a number of overflow events.

Five percent of the average annual demand can be estimated:

Where:

- D0.05 is five percent of the average annual demand (L)

- Pd is the daily demand per person (L)

- n is the number of occupants

Then the following calculations are based upon two criteria:

- A design rainfall depth is to be captured entirely by the RWH system.

- The average annual demand (D) is greater than the average annual yield (Y) from the catchment.

When \(Y_{0.05}/D_{0.05}<0.33\), the storage volume required can be estimated:

Where:

- VS is the volume of storage required (L)

- Ac is the catchment area (m2)

- Cvol,E is the design storm runoff coefficient for the catchment

- Rd is the design storm rainfall depth (mm), and

- e is the efficiency of the pre-storage filter.

- Careful catchment selection means that the runoff coefficient, for an individual rainstorm event (Cvol, E) should be 0.9 or greater.

Finally, when \(0.33<Y_{0.05}/D_{0.05}<0.7\), the total storage required can be estimated by adding Y0.05:

STEP Rainwater Harvesting Tool[edit]

The Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program have produced a rainwater harvesting design and costing tool specific to Ontario. The tool is in a simple to use Excel format and is free to download.

STEP Treatment Train Tool[edit]

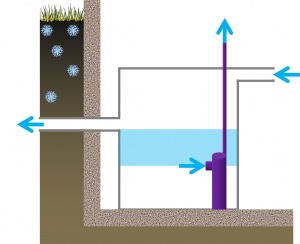

Cistern dimensions[edit]

The connections into and out of a rainwater cistern can have a dramatic effect on the actual usable volume. The only usable water within the cistern is that above the height of the pump intake, and below the invert of the overflow outlet. This dimension can easily become constrained where the outlet must lie beneath the frost line and where a high powered pump is required to elevate the water many storeys.

- The depth of storage between the elevation of the inlet and overflow is unusable space, so the overflow should be located towards the top of the cistern.

- The depth of storage beneath the pump inlet is unusable, but may also be a useful zone for sediment to settle. A custom or cast-in-place vault could minimise this unused volume by tapering towards the the base.

Catchments

Decisions need to be made about the selection and grading of catchments. If one catchment is very large, can it be regraded to drain to two or more outlets? Is it desirable to capture both rooftop water and other stormwater? This will may determine the quality improvements required to use the water. See table below, which illustrates the higher treatment required for storm water (i.e. non-rooftop).

Cisterns

Preformed above-ground tanks are usually constructed from polyethylene or galvanized steel. They are available with storage capacity up to around 50,000 L. Preformed below-ground tanks may be constructed from reinforced fiberglass or concrete. Fiberglass tanks are available up to around 150,000 L. Concrete vaults can be constructed in almost any size. Wooden tanks are less common but are also available and permitted in the regulations.

As a standing body of freshwater, RWH cisterns present ideal habitat for mosquitoes. Mosquitoes should be prevented from entering by using a mesh screen on all openings. Larvicides may be added when the water is only to be used for irrigation purposes. To prevent algal growth, the cistern must be opaque or otherwise protect the water from light.

Plumbing and Regulation

The current Ontario Building Code requires that rainwater harvesting systems are designed, constructed and installed to conform to good engineering practice. References are made to ASHRAE, ASPE[4] and CSA [5] guides for plumbing detailing.

These guides focus on ensuring that the rainwater does not contaminate or become mistaken for the municipal drinking water supply. Similarly, rainwater must be prevented from becoming contaminated from the sewer. In both cases, an air gap or a back-flow preventer is required.

<panelInfo>

</panelInfo>

Performance[edit]

Water Quantity

In theory a large enough RWH cistern could retain 100% of a single storm. However, sizing a stormwater cistern must account for regulatory requirements, available space, budget, and draw-down i.e. rate of use. If a RWH system is being employed for storm water control, the cistern size will typically be greater than that for optimized potable water use reduction.

In 2007-2010 STEP monitored and modelled three rainwater harvesting systems in the Greater Toronto Area[6]. Each system was sized to balance stormwater management objectives with with potable water use reduction for irrigation and toilet flushing. Key findings include:

- Around 18-20% of the precipitation was lost directly from the rooftop.

- Annual stormwater capture varied between 18 and 42 %.

Water Quality

The important water quality parameters for harvested rainwater differ from other types of LID. This is due to the potential for direct human contact, rather than environmental discharge. As of July 2017, the CSA and ICC are finalizing a standard[7] which specifies different water quality treatments according to the source (roof runoff versus stormwater runoff) and the intended use.

Tier 1 end uses are most readily achievable, requiring only that larger particles are filtered out of the water. Removing the bulk of the solid particles reduces the nutrient concentration in the water and prevents clogging of the water distribution system. Toilet and urinal flushing are the next most popular use of harvested rainwater. If flushing or other higher tier end uses are desired, disinfection of some type is required and consideration may be given to colour and odour of the water. Technologies for achieving higher standards of water quality include:

- Ultraviolet (UV) disinfection requires additional filtration to remove particles so that the light can penetrate the water and destroy the viruses and bacteria,

- Chlorine disinfection also requires additional filtration to remove larger particles,

- Micro- or Ultra- filtration uses such fine membranes that the vast majority of harmful viruses, bacteria etc. are excluded from the water directly.

| Application | Roof runoff pathogen reduction | Stormwater pathogen reduction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End Use Tier | Example uses | Viruses | Bacteria | Protazoa | Viruses | Bacteria | Protazoa |

| 1 |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 |

|

0 | 99% | 99% | 99.99% | 99.99% | 99.9% |

| HVAC systems | In accordance with ASHRAE 188 | ||||||

| 3 |

|

99.9% | 99.9% | 99.9% | 99.99% | 99.99% | 99.99% |

| 4 |

|

0 | 99.999% | 99.999% | Outside of the scope of the CSA standard | ||

Source Water Quality[edit]

A study of many types of roof surfaces in Texas found:

- 'Cool' membrane, concrete tile, and metal roofs all produced water of similar good quality for non-potable use,

- The runoff water from asphalt shingle and green roofs contained significantly more dissolved organic carbon (DOC). The DOC can add a yellow colour to the water. If the water is treated with chlorine, for drinking purposes, DOC can produce toxic compounds[1].

Research in Hamilton, ON assessed the water quality of rain collected from three highly reflective 'cool roof' membranes[2]. Key findings:

- The water was free from significant contamination with by-products of plastic manufacture and did not show elevated levels of the five metals tested.

- Increased microbiological contamination was found in runoff from roof areas where ponding occurred.

Note: Increased microbiological contamination in roof runoff is also associated with warmer weather [3].

Incentives and Credits[edit]

In Ontario

City of Mississauga

The City of Mississauga has a stormwater management credit program which includes RWH as one of their recommended site strategies[8].

LEED BD + C v. 4

Water Efficiency: Rainwater management (up to 3 points)

Note that for lines 1. and 2. preference is given to LID that 'best replicates natural site hydrology':

- Two points (or 1 point for Healthcare) will be awarded if the project manages "the runoff from the developed site for the 95th percentile of regional or local rainfall events."

- Three points (or 2 points for Healthcare) will be awarded if the project manages "the runoff from the developed site for the 98th percentile of regional or local rainfall events."

OR For zero-lot-line projects only, 3 points (or 2 points for Healthcare) will be awarded if the project manages "the runoff from the developed site for the 85th percentile of regional or local rainfall events."

This last clause relating to zero-lot-line projects is where RWH may prove most applicable compared to other LID.Pilot Credits: Whole Project Water Use Reduction (up to 10 points)

This pilot credit requires whole building water use modeling to demonstrate reduced water use compared to a baseline model.

A sliding scale awards between 1 point for 10% reduction to 10 points for 65% reduction.

Making this kind of water use reduction would typically require reuse of greywater as well as an optimized RWH plan.

See Also[edit]

External Links[edit]

Rainwater harvesting: External links

- REDIRECT Special:ArticleFeedbackv5

- ↑ Mendez CB, Klenzendorf JB, Afshar BR, et al. The effect of roofing material on the quality of harvested rainwater. Water Res. 2011;45(5):2049-2059. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.12.015.

- ↑ Cupido, A., B. Baetz, Y. Guo, and A. Robertson. 2012. An evaluation of rainwater runoff quality from selected white roof membranes. doi: 10.2166/wqrjc.2012.011.

- ↑ Vialle C, Sablayrolles C, Lovera M, Jacob S, Huau MC, Montrejaud-Vignoles M. Monitoring of water quality from roof runoff: Interpretation using multivariate analysis. Water Res. 2011;45(12):3765-3775. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.04.029.