Difference between revisions of "Inspection and maintenance"

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

- Copy of McMaster Training course and link to the course | - Copy of McMaster Training course and link to the course | ||

[[File:50 year life cycle LID BMP.PNG | [[File:50 year life cycle LID BMP.PNG|700px]]<br> | ||

</br> | |||

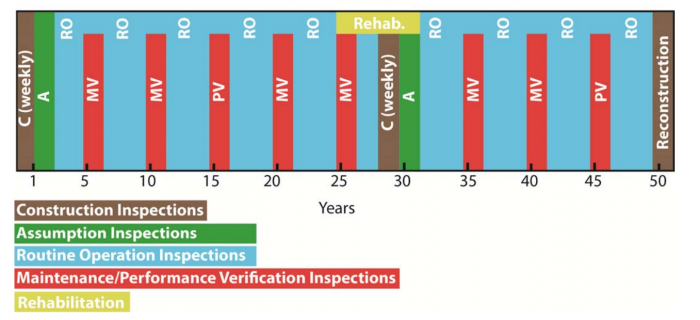

The above figure depicts a typical inspection timeline for LID BMPs over a 50 year life cycle. (TRCA, 2016).<ref>TRCA. 2016. Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Practice Inspection and Maintenance Guide. Version 1.0. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2016/08/LID-IM-Guide-2016-1.pdf</ref> | |||

==Training Requirements== | ==Training Requirements== | ||

Revision as of 21:10, 11 April 2022

Overview[edit]

Integration of Low Impact Development (LID) best management practices (BMPs) into stormwater management (SWM) systems is widely advocated to better address the potential stormwater-related impacts of urbanization on the health of receiving waters. A substantial amount of guidance is available on the planning and design of LID BMPs (CVC & TRCA, 2010)[1] and their construction (CVC, 2012)[2] and some municipalities and conservation authorities commonly require them to be a part of new SWM systems.

However, even with sound design, LID BMPs may not provide the intended level of treatment if they are not installed properly or protected from damage during construction. Experiences with early applications have shown that failures are often due to:

- Practices not being constructed as designed or with specified materials

- Lack of erosion and sediment controls (ESCs) during construction; and/or

- Lack of rigorous inspection prior to assumption.

A 2009 survey of stormwater BMPs in the James River watershed (Virginia) by the Center for Watershed Protection found approximately half (47%) of the 72 BMPs deviated in one or more ways from the original design, or were receiving inadequate maintenance (CWP, 2009)[3]. Similar results have been revealed from surveys of stormwater detention ponds in Ontario (Drake et al., 2008[4]; LSRCA, 2011[5]), highlighting the need for thorough inspections of BMPs prior to assumption and a proactive approach to stormwater infrastructure operation and maintenance. Therefore, it is important to conduct timely inspections during construction and detailed inspection and testing prior to assumption to ensure that LID BMPs are:

- Built according to approved plans and specifications

- Installed at an appropriate time during overall site construction and with protective measures to minimize risk of siltation or damage; and

- Fully operational and not in need of maintenance or repair at the time of assumption by the property owner or manager.

Like all stormwater BMPs, LID practices are designed to retain pollutants carried by urban runoff and all have a finite capacity to perform this function in the absence of maintenance, until their treatment performance declines or they no longer function as intended. Their functional and treatment performance will only be sustained over the long term if they are adequately inspected and maintained. Under the Ontario Water Resources Act, provincial approvals for SWM facilities and BMPs (i.e., Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change’s Environmental Compliance Approvals process) typically make the property owner responsible for all inspection and maintenance tasks and associated record keeping (Zizzo et al., 2014[6]). A proactive, routine inspection and maintenance program will also:

- Identify maintenance issues before they significantly affect the function of the BMP

- Help to optimize the use of program resources by providing the feedback needed to determine when structural repairs are needed and to adjust the frequency of routine inspection and maintenance tasks where it is warranted; and

- Help to improve BMP design guidance and develop standards.

Unlike conventional SWM systems that centralize treatment facilities in few locations on publicly owned land (e.g., detention ponds) an LID design approach involves smaller scale practices distributed throughout the drainage area, potentially on both public and private land. Implementing an LID approach to system design has major implications on municipalities and property managers with respect to operating the stormwater infrastructure they are responsible for, as it increases the number and types of BMPs to be tracked, inspected and maintained.

This Inspection and Maintenance (I&M) page is intended to assist users (municipalities, consultants and property managers) with developing their capacity to integrate LID SWM BMPs into their projects and/or larger infrastructure asset management programs. Sections below provide:

- Guidance on designing an effective LID BMP inspection and maintenance program

- Based on experiences and advice from jurisdictions in Canada and the United States, and adapted to an Ontario context.

- Recommended standard protocols for inspection, testing and maintenance of the following types of structural LID BMPs:

- Bioretention and dry swales

- Enhanced swales

- Vegetated filter strips and soil amendment areas

- Permeable pavements

- Underground infiltration systems

- Green roofs; and

- Rainwater cisterns

- Guidance on recommended inspection, testing and maintenance tasks specific to each BMP type

- A summarization of staff skills and equipment required to complete them

- sampling and testing procedures and protocols

- Estimated costs over a 50 year BMP life cycle.

Drawing upon the information provided on this; and its subsequent page(s) municipalities and property managers will be better able to design or adapt their infrastructure asset management programs to include LID BMPs effectively, and understand the tasks, procedures and estimated costs associated in adequately inspecting and maintaining them.

LID Practices' Inspection & Maintenance[edit]

Inspection & Maintenance Terminology[edit]

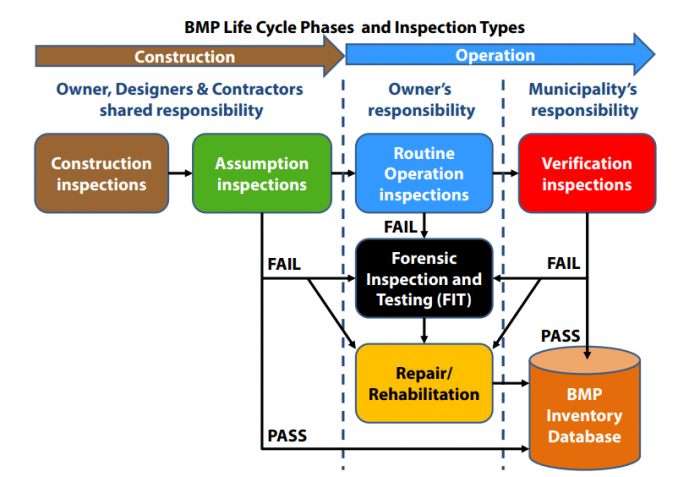

Construction Inspections[edit]

Construction inspections should be a shared responsibility between the property owner or their project manager, the designers (i.e., engineer and landscape designer) and the construction contractors. Many municipalities already conduct some form of inspection of infrastructure they will eventually assume during its construction. Those that do not, might choose to work with internal departments (e.g., road or building inspectors, parks/landscaping inspectors) or other agencies (e.g., conservation authorities) that routinely conduct inspections at active construction sites. With adequate training and staff resources, it might be possible to integrate stormwater BMP inspection duties during construction into existing programs. If the workload or skill set needed is beyond what existing programs can handle, or the timing of other types of inspections do not coincide with critical timing of BMP construction inspections, hiring of trained contractors or allocation of dedicated stormwater infrastructure program staff may be necessary.

The frequency of Construction inspections may be determined by the municipal stormwater infrastructure program policy or may be general program targets (e.g., weekly, after large storm events, as triggered by construction milestones and hand-off points between different contractors). At a minimum, inspections should occur just prior to the onset of BMP construction to ensure compliance with erosion and sediment control plans and after any large storm event (e.g., 15 mm rainfall depth or greater) during the BMP construction period.

Feedback from Construction inspections should be used to correct any issues associated with BMP installation or Erosion Sediment Controls (ESCs) and to identify when changes to the installation procedures, ESCs or BMP design are needed due to site circumstances or complications encountered. In cases where the project proponent or property owner uses a formal bidding process to select a construction contractor, opportunities exist to include special provisions in tender documents or contracts that will help ensure that LID BMPs receive adequate inspection and maintenance during construction.

Special provisions in tender documents or construction contracts related to LID BMP installation that can be included to help ensure adequate inspection and maintenance during construction include the following (CVC, 2014)[7]:

- Clearly outline the work required to install each type of BMP and list the activities involved

- Detail the product and material specifications and whether approved equivalents are permissible

- Outline installation procedures for each type of BMP and critical points in the sequence of activities when Construction inspections are required before proceeding further (e.g., checking elevations and grades of excavations and pipes prior to backfilling)

- State any testing requirements or quality assurance documentation for construction materials that must be received and accepted prior to delivering the material to the site (e.g., filter media, aggregate material);

- Specify maintenance tasks the contractor is responsible for, including procedures and conditions for when or how frequently they need to be done (e.g., sediment removal from BMP pretreatment devices and conveyance structures, maintenance of plantings over the warranty/establishment period).

For more detail and examples of how special provisions relating to LID BMPs can be used in construction tender documents and contracts refer to Credit Valley Conservation’s Grey to Green Retrofit Guides (CVC, 2014.)[8]

Assumption Inspections[edit]

Assumption inspections should be a shared responsibility between the property owner or their project manager, the designers (engineering and landscape design professionals) and construction contractors involved in the project. When the municipality is not the property owner, they may choose to not be involved in performing or reviewing such inspection work but should still receive copies of Assumption inspection records so that an inventory database of permanent stormwater BMPs on private property that connect to municipal infrastructure can be developed and maintained. Other terms for such inspections include deficiency, project acceptance or certification inspections.

At a minimum, Assumption inspections should be performed:

- Immediately after site construction (including landscaping) ends (i.e., the deficiency inspection) prior to substantial completion of construction, release of performance bonds (if applicable) and beginning of the warranty or establishment period, and;

- Prior to termination of the warranty or establishment period (e.g., 2 years after substantial completion of construction), release of any maintenance holdbacks (if applicable) and assumption by the property owner.

Feedback from inspections should be used to correct any deviations from the approved design or material specifications not approved through change orders, deficiencies in BMP function due to how it was designed or installed and to initiate follow up to replace failed plantings that are under warranty. Once satisfactory results from Assumption inspections are achieved the performance bond(s) are released and the property owner assumes the BMP and becomes responsible for inspection and maintenance tasks. At this stage, documentation of results from Assumption inspections, and records describing the maintenance tasks performed over the establishment or warranty period should be provided by the consultant or municipality to the property owner. The municipality should also receive this information if they are not the inspector or owner and the BMP qualifies for inclusion in their program. There are a variety of approaches to ensuring thorough and satisfactory Assumption inspections of LID BMPs are completed prior to assumption by the property owner but the following contractual and administrative strategies should be considered.

Performance Bonds, Letters of Credit and Cash Sureties[edit]

- A common method for ensuring BMPs are ready for acceptance/assumption at the end of construction and prior to termination of the construction contract is to require that a performance bond, letter of credit or cash surety be submitted by the contractor to the property owner as a condition of the contract, ideally in an amount equivalent to the full cost of the work.

- In such cases, construction contracts should specifically require that thorough inspection and testing of the BMPs be completed to the satisfaction of the property owner or their project manager and design consultants as a condition of Assumption, contract termination and release of the performance bond, letter of credit or cash surety.

Holdbacks in Construction Tenders or Contracts[edit]

- The property owner can specify in construction tenders or contracts to retain a certain percentage of the total value of the work done for a period of 12 months from the date of final completion.

- In such cases, construction contracts should specifically require that thorough inspection and testing of the BMPs be completed to the satisfaction of the property owner or their project manager, design consultants and construction contractors as a condition of Assumption, contract termination and release of the holdback amount.

- In such cases, construction contracts should specifically require that thorough inspection and testing of the BMPs be completed to the satisfaction of the property owner or their project manager, design consultants and construction contractors as a condition of Assumption, contract termination and release of the holdback amount.

Routine Operation Inspections[edit]

Routine Operation inspections should be the responsibility of the property owner or their contractors. At a minimum, Routine Operation inspections should occur annually, but twice annually (in spring and fall seasons) is preferable for vegetated BMPs. More frequent inspections may be warranted for highly visible BMPs, those receiving drainage from high traffic areas (vehicle or pedestrian), or those designed with larger than recommended impervious drainage area to pervious BMP footprint area ratio (i.e., I:P ratio). Feedback from inspections should be used to immediately address routine maintenance needs, schedule structural repairs or further investigations into potential problems with BMP function and to adjust the preset schedule of routine maintenance tasks to optimize the use of program resources.

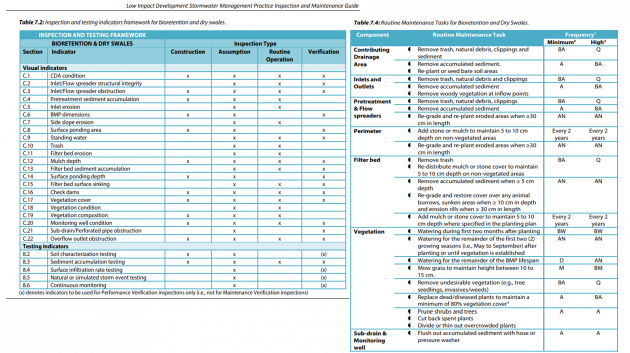

Each LID BMP's I&M page will provide further guidance on Routine Operation inspection objectives and tasks, associated timing of said inspections and specific skills required by inspectors, along with key components to be inspected and what visual and testing indicators should be used, and recommended minimum frequencies.

Furthermore, blank template field data forms for recording inspection results are provided within each section as well to be downloaded and used for personal use.

Verification Inspections[edit]

Verification inspections should be the responsibility of the municipality or be a shared responsibility between the property owner (e.g., hires consultant to perform and document the inspections) and municipality (e.g., approves and tracks documentation). A Verification inspection could replace one Routine Operation inspection that the property owner is responsible for that year.

Maintenance Verification[edit]

- For permanent BMPs designed and installed to meet regulatory or municipal program requirements, inspections to verify compliance with ECA or maintenance agreement conditions and associated BMP specific inspection and maintenance plans (i.e., Maintenance Verification inspections) should occur on five (5) year intervals beginning after the date of assumption.

Maintenance Verification inspections should also be performed when property ownership changes to ensure the new owner is not assuming a BMP that has been neglected by the previous owner, and to help educate the owner about their inspection and maintenance and record keeping responsibilities. Inspection and testing to verify that functional performance remains acceptable (i.e., Performance Verification inspections)should at a minimum, occur on fifteen (15) year intervals beginning after the date of assumption.

Performance Verification[edit]

- More frequent Performance Verification inspections may be warranted for BMPs draining to highly sensitive receiving waters or habitat of species at risk. Testing of functional performance (e.g., surface infiltration rate testing, natural or simulated storm event testing, continuous monitoring) is done in addition to Maintenance Verification inspection indicators (i.e., visual indicators and sediment accumulation testing).

Feedback from Maintenance and Performance Verification inspections should be used to initiate compliance enforcement actions if warranted and schedule structural repairs or further investigations into observed problems with BMP function. Each LID BMP's I&M page will provide further guidance on Verification inspection objectives and tasks, timing of inspections and skills required by inspectors along with guidance to what key components should be inspected and what visual and testing indicators should be used along with available structural repair options.

Furthermore, blank template field data forms for recording inspection results are provided within each section as well to be downloaded and used for personal use.

Forensic Inspection and Testing (FIT)[edit]

When results from other types of inspections identify a potential problem with BMP function, Forensic Inspection and Testing (FIT) work is undertaken as a follow-up task to investigate the situation and come up with a plan to address any confirmed problems. FIT work involves the application of a similar set of inspection and testing indicators as those used in Performance Verification inspections, but focuses on diagnosing suspected problems with the following objectives in mind:

- Confirm whether or not problems with BMP function exist;

- Identify the causes of confirmed problems;

- Determine corrective actions needed.

Forensic Inspection and Testing is done on an as-needed basis, as follow-up from other types of inspections where potential problems with BMP function are suspected. These specialized inspections must be a shared responsibility of the property owner (e.g., hires consultant to perform and document the inspections) and municipality (e.g., approves and tracks documentation), as they will determine what corrective actions are needed, which could involve structural repairs, rehabilitation or replacement of the BMP.

Results of FIT work and any corrective actions that follow it should be recorded in BMP inventory and tracking databases maintained by the municipality. FIT work should be performed by individuals trained in, and experienced with inspecting LID SWM BMPs, landscaping, and diagnosing the causes of observed problems with function. Individuals must also be trained in the use of soil sampling and testing and environmental monitoring equipment (e.g., engineer, engineering or environmental technologist). The results of FIT work should be provided to the property owner along with any recommendations for follow-up tasks that arise from them and timeframes for completing them. If the property owner fails to complete follow-up tasks within the timeframe specified by the municipality, enforcement actions are warranted. The nature and severity of enforcement actions will differ depending on the municipality but may include loss of stormwater utility fee credit, billing the property owner for necessary maintenance or repair work completed by the municipality or their contractors, or fines.

Life Cycle and Inspection[edit]

- Copy of McMaster Training course and link to the course

The above figure depicts a typical inspection timeline for LID BMPs over a 50 year life cycle. (TRCA, 2016).[10]

Training Requirements[edit]

(Add - {{ }}) on main site - widgets do not work yet on dev site. #widget:YouTube|id=U0b6g-0K1oM

Key Considerations During BMP Design and Planning[edit]

Testing[edit]

External Links[edit]

Embedded Guide[edit]

This guide is focused on planning and design. In many places you will find tips to design structures with considerations for how to facilitate future maintenance.

But to get detailed information from STEP on the inspection and maintenance of LID practices, please see our complete guide here or embedded below:

References[edit]

- ↑ CVC and TRCA. 2010. Low impact Development Stormwater Management Planning and Design Guide. Version 1.0. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2013/01/LID-SWM-Guide-v1.0_2010_1_no-appendices.pdf

- ↑ CVC. 2012. Low Impact Development Construction Guide. Version 1.0. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/CVC-LID-Construction-Guide-Book.pdf

- ↑ Centre for Watershed Protection. 2009. Technical Report Stormwater BMPs in Virginia’s James River Basin: An Assessment of Field Conditions & Programs (part of the Extreme BMP Makeover project). Prepared by David Hirschman, Laurel Woodworth, and Sadie Drescher Center for Watershed Protection, Inc. Final Draft. June 2009. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/channel_files/19219/cwp_james_river_tech_report_final_draft_062509.pdf.pdf

- ↑ Drake, J. Guo, Y. 2008. Maintenance of Wet Stormwater Ponds in Ontario. Canadian Water Resources Journal. 33 (4): 351-368. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.4296/cwrj3304351?needAccess=true

- ↑ Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA). 2011. Stormwater Pond Maintenance and Anoxic Conditions Investigation. Final Report. Newmarket, ON. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2015/01/LSRCA-Stormwater-Maintenance-and-Anoxic-Conditions-2011.pdf

- ↑ Zizzo, L.L., Allan, T., Kocherga, A. 2014. Stormwater Management in Ontario: Legal Issues In a Changing Climate – A Report for the Credit Valley Conservation Authority. Toronto, ON. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Stormwater-Management-in-Ontario_Legal-Issues-in-a-Changing-Climate_2014.04.29.pdf

- ↑ Credit Valley Conservation (CVC). 2014. Grey to Green Road Retrofits: Optimizing Your Infrastructure Assets Through Low Impact Development. Mississauga, ON. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Grey-to-Green-Road-ROW-Retrofits-Complete_1.pdf

- ↑ Credit Valley Conservation (CVC). 2014. Grey to Green Road Retrofits: Optimizing Your Infrastructure Assets Through Low Impact Development. Mississauga, ON. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Grey-to-Green-Road-ROW-Retrofits-Complete_1.pdf

- ↑ TRCA. 2016. Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Practice Inspection and Maintenance Guide. Version 1.0. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2016/08/LID-IM-Guide-2016-1.pdf

- ↑ TRCA. 2016. Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Practice Inspection and Maintenance Guide. Version 1.0. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2016/08/LID-IM-Guide-2016-1.pdf