Difference between revisions of "Inspection and Maintenance: Rainwater Harvesting"

| Line 350: | Line 350: | ||

[[File:Life cycle costs RWH.PNG|thumb|center|400px|Construction and life cycle cost estimates for rainwater harvesting features features with partial infiltration (in 2016 $ figures) (TRCA, 2018)<ref name="example1" />.]]<br> | [[File:Life cycle costs RWH.PNG|thumb|center|400px|Construction and life cycle cost estimates for rainwater harvesting features features with partial infiltration (in 2016 $ figures) (TRCA, 2018)<ref name="example1" />.]]<br> | ||

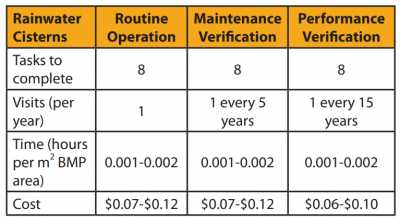

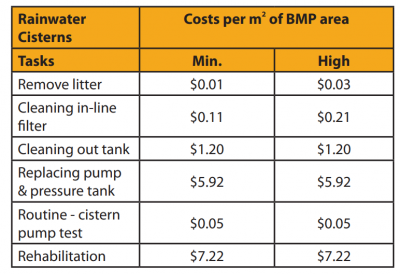

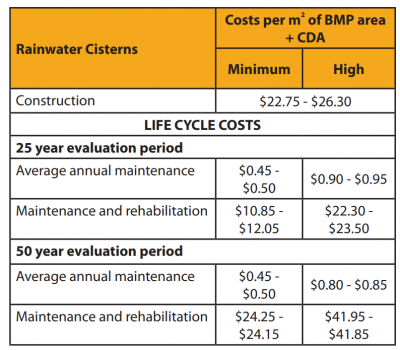

Estimates of the life cycle costs of inspection and maintenance have been produced using the latest version of the [[Cost analysis resources|LID Life Cycle Costing Tool]] for two design variations ( | Estimates of the life cycle costs of inspection and maintenance have been produced using the latest version of the [[Cost analysis resources|LID Life Cycle Costing Tool]] for two design variations (underground concrete cistern; and indoor plastic cistern systems) to assist stormwater infrastructure planners, designers and asset managers with planning and preparing budgets for potential LID features. | ||

Assumptions for the above costs and the following table below are based on the following: | Assumptions for the above costs and the following table below are based on the following: | ||

* | *For rainwater cisterns it is assumed that no rehabilitation work will be needed to maintain acceptable storage and drainage performance over a 50 year period of operation (40 for plastic cisterns), given that pretreatment devices are in place and are being adequately maintained. The annual average maintenance cost value represents an average of routine maintenance tasks, as outlined in Table 7.28. All cost value estimates represent the NPV as the calculation takes into account average annual interest (2%) and discount (3%) rates over the evaluation time periods. | ||

**Costs include overhead and inflation to represent contractor pricing. It was assumed the practice is part of a new development (i.e., not a retrofit), thereby excluding (de)mobilization costs unless a particular piece of equipment would not normally have been present at the site. Additionally, it was assumed that excavated soil associated with construction of the BMP would be reused elsewhere on site. Overhead costs were presumed to consist of construction management (4.5%), design (2.5%), small tools (0.5%), clean up (0.3%) and other (2.2%). | **Costs include overhead and inflation to represent contractor pricing. It was assumed the practice is part of a new development (i.e., not a retrofit), thereby excluding (de)mobilization costs unless a particular piece of equipment would not normally have been present at the site. Additionally, it was assumed that excavated soil associated with construction of the BMP would be reused elsewhere on site. Overhead costs were presumed to consist of construction management (4.5%), design (2.5%), small tools (0.5%), clean up (0.3%) and other (2.2%). | ||

*For maintenance frequencies and requirements and the life span of each practice are based on both literature and practical experience. Life cycle and associated maintenance costs are evaluated over a 50 year timeframe, which is the typical period over which infrastructure decisions are made. | *For maintenance frequencies and requirements and the life span of each practice are based on both literature and practical experience. Life cycle and associated maintenance costs are evaluated over a 50 year timeframe, which is the typical period over which infrastructure decisions are made. | ||

Revision as of 18:29, 16 August 2022

Overview[edit]

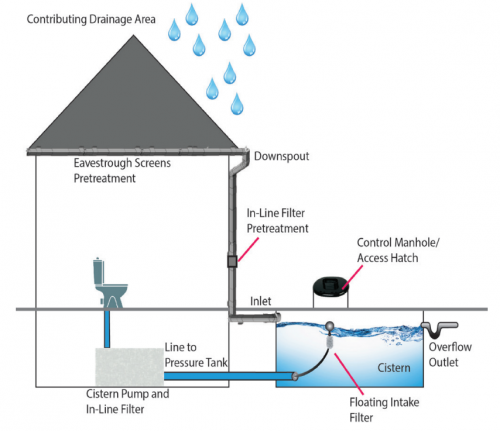

Rainwater harvesting/cisterns uses storage structures that can be installed either:

- Below-ground;

- Indoors that provide a year-round water source; or,

- Aboveground tanks and rain barrels that can only be used seasonally and must be taken out of service for the winter.

Rainwater cisterns can range in size from about 750 to 40,000 litres+ and may be constructed from fiberglass, plastic, metal or concrete.

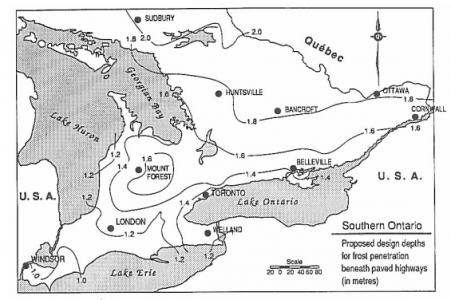

Underground cisterns are most often installed to a depth below the maximum frost penetration depth (generally 1.2 m in Southern Ontario) (Armstrong and Csathy, 1963; Ministry of Transportation, 2013)[2][3] to ensure they can be used year-round. A pump is used to deliver the stored water to the hose bibs or fixtures where it is utilized. Water that is in excess of the storage capacity of the cistern overflows to an adjacent drainage system (e.g., other BMP or municipal storm sewer) via an overflow outlet structure and pipe. Cisterns that are drawn upon for indoor water uses (e.g., toilet flushing) will also feature water level sensors and the means of adding municipal water during extended periods of dry weather or winter when stormwater does not meet the demand (i.e., make-up water supply system). They may also include in-line devices to filter stored cistern water prior to delivery at hose bibs or fixtures.

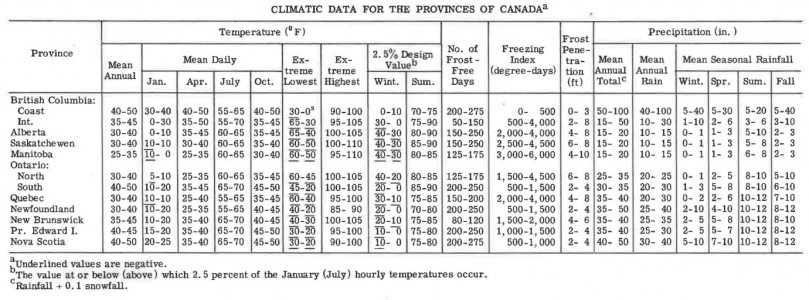

Frost penetration in southern Ontario shown to be 2 - 4 ft. deep (Armstrong and Csathy, 1963)[4].

Design depth showing further detailed frost penetration contour lines for southern Ontario ranging from 1.0 - 2.0m deep (Ministry of Transportation, 2013)[5]

Some of the benefits of green roofs include:

- The ability to reduce the quantity of pollutants and runoff being discharged to municipal storm sewers and receiving waters (i.e., rivers, lakes and wetlands);

- Underground and indoor cisterns can be used year-round and located below parking lots, roads, plazas, parkland, landscaped areas or within buildings themselves.

- Can reduce a large commercial building or residential home's water usage significantly if used for non-potable needs

Key components of Underground Infiltration Systems to pay close attention to are the:

Associated Practices[edit]

- Rain Barrels Rain barrels are an above ground form of rainwater harvesting, typically used in residential settings. The precipitation flows from the roof, to the guttering and down the downspout before being diverted to the rain barrel for storage.

- Downspout disconnection Downspout disconnections are common in many older urban centers. They require that residents retroactively disconnect their downspouts from the municipal sewer system. This is due to older sewer systems being undersized for the combined flow of sanitary waste and stormwater.

- Blue roofs are systems that temporarily capture rainwater using the roof as storage and allow it to evaporate and/or to be used for non-potable requirements (i.e. irrigation, toilet flushing, truck washing) and ultimately offset potable water demands.

Inspection and Testing Framework[edit]

Component |

Indicators |

Construction Inspection |

Assumption Inspection |

Routine Operation Inspection |

Verification Inspection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributing Drainage Area | |||||

| CDA Condition | x | x | x | x | |

| Inlet | |||||

| Inlet/Flow spreader structural integrity | x | x | x | ||

| Inlet/Flow spreader obstruction | x | x | x | x | |

| Pretreatment sediment accumulation | x | x | x | ||

| Perimeter | |||||

| BMP dimensions | x | x | x | ||

| Overflow outlets | |||||

| Overflow outlet obstruction | x | x | x | x | |

| Control structure condition | x | x | x | x | |

| Cistern | |||||

| Cistern structural integrity | x | x | x | x | |

| Cistern sediment accumulation | x | x | x | x |

Component |

Indicators |

Construction Inspection |

Assumption Inspection |

Routine Operation Inspection |

Verification Inspection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing Indicators | ||||||

| Sediment accumulation testing | x | x | x | x | ||

| Cistern pump testing | x | x | (x) | |||

| Note: (x) denotes indicators to be used for Performance Verification inspections only (i.e., not for Maintenance Verification inspections) | ||||||

Construction Inspection Tasks[edit]

Construction inspections take place during several points in the construction sequence, specific to the type of LID BMP, but at a minimum should be done weekly and include the following:

- During site preparation, prior to BMP excavation and grading to ensure that adequate ESCs and flow diversion devices are in place and confirm that construction materials meet design specifications

- At completion of excavation and grading, prior to backfilling and installation of cistern and pipes to ensure depths, slopes and elevations are acceptable

- At completion of installation of cistern and pipes, prior to completion of backfilling to ensure slopes and elevations are acceptable

- Prior to hand-off points in the construction sequence when the contractor responsible for the work changes (i.e., hand-offs between the storm sewer servicing, paving, building and landscaping contractors)

- After every large storm event (e.g., 15 mm rainfall depth or greater) to ensure Erosion Sediment Controls (ESCs) and pretreatment or flow diversion devices are functioning and adequately maintained. View the table below, which describes critical points during the construction sequence when inspections should be performed prior to proceeding further. You can also download and print the table here

Construction Sequence Step & Timing |

Inspection Item |

Observations* |

|---|---|---|

| Site Preparation - after site clearing and grading, prior to BMP excavation and grading | Natural heritage system and tree protection areas remain fenced off | |

| ESCs protecting BMP layout area are installed properly | ||

| CDA is stabilized or runoff is diverted around BMP layout area | ||

| BMP layout area has been cleared and is staked/delineated | ||

| Benchmark elevation(s) are established nearby | ||

| Construction materials have been confirmed to meet design specifications | ||

| BMP Excavation and Grading - prior to backfilling and installation of cistern and conveyance pipes | Excavation location, footprint, depth and slopes are acceptable | |

| Installations of underdrains/sub-drain pipes (location, elevation, slope) are acceptable | ||

| BMP Installation – after installation of pipes/sewers, prior to backfilling | Installation of structural components (i.e., pretreatment devices, inlets, cistern, overflow outlet, pump, make-up water supply and backflow preventer valve, control manhole/ access hatch) are acceptable and functioning |

Routine Maintenance - Key Components and I&M Tasks[edit]

Regular inspections (twice annually, at a minimum) done as part of routine maintenance tasks over the operating phase of the BMP life cycle to determine if maintenance task frequencies are adequate and determine when rehabilitation or further investigations into BMP function are warranted.

Table below describes routine maintenance tasks for rainwater harvesting practices, organized by BMP component, along with recommended minimum frequencies. It also suggests higher frequencies for certain tasks that may be warranted for cisterns that receive flows from large roof drainage areas or roofs with mature trees near them. Tasks involving removal of debris, sediment and trash may need to be done more frequently in such contexts.

| Component | Description | Inspection & Maintenance Tasks | (Pass) Photo Example | (Fail) Photo Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributing Drainage Area (CDA) |

Roof area(s) from which runoff directed to the BMP originates. |

|

||

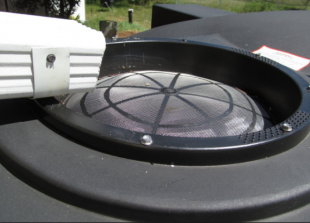

| Pretreatment |

Devices prevent debris and sediment from entering the BMP. Includes eavestrough or downspout screens, first flush diverters or filters on pipes leading to or from the cistern. Reduce the risk of obstructing inlets, intakes or overflow outlet pipes and excessive sediment accumulation. |

|

||

| Inlets |

Pipes connected to eavestroughs or roof drains that deliver water to the BMP. May also include a pipe connected to the municipal water supply line for maintaining cistern water level during dry weather. |

|

||

| Access Hatch |

Hatch, manhole or lid that provides access to the interior of the water storage structure. |

|

||

| Cistern or rain barrel |

The water storage structure (e.g., concrete vault, fiberglass, plastic or metal tank, rain barrel). |

|

||

| Pump |

Pressurized device used to deliver stored rainwater to the hose bibs. |

|

Installation of structural components and current operating level are acceptable and functioning in clean and easily accessible condition as seen here (Photo Source: Meir, 2021)[7] |

With prolonged usage, the pump capacity declines, causing a reduction in flow rate overall. If the pump is not creating sufficient pressure, and the flow rate is below the design specification, servicing of the pump by a skilled technician should be scheduled (Photo Source: Rapid Plumbing Group Pty Ltd., 2022).[8] |

| Filter |

Cisterns may include an in-line filter device on the intake pipe or prior to delivery of rainwater to hose bibs. |

|

||

| Overflow Outlet |

Pipe connected to the cistern or rain barrel that conveys overflows to another drainage system (e.g., municipal storm sewer or other BMP). |

|

Tips to Preserve Basic BMP Function[edit]

- Routinely check the water delivered to hose bibs or fixtures for turbidity or discolouration which could indicate excessive sediment accumulation in the cistern or failure of pretreatment devices or filters.

- Include a filtration device to treat stored water prior to delivery to hose bibs or fixtures as part of the intake/distribution system and clean filters at the same frequency as pretreatment devices.

- If the overflow outlet discharges at grade, the pipe opening should be covered with a coarse screen to prevent entry by insects and animals.

- Provide a means of draining the cistern by gravity to make inspection and maintenance work that requires drainage of the BMP easier to perform.

- Remove accumulated sediment from a large cistern using a pressure washer or hydro-vac truck equipped with a JetVac nozzle to scour and direct sediment to a collection point for removal by vacuuming; for small cisterns, a garden hose and wet shop vacuum may be used.

Rehabilitation & Repair[edit]

Table below provides guidance on rehabilitation and repair work specific to rainwater harvesting systems and rain barrels organized according to BMP component. For more detailed guidance on troubleshooting rainwater harvesting systems refer to Ontario Guidelines for Residential Rainwater Harvesting Systems - Handbook (Despins, 2010)[9] and the Canadian Guidelines for Residential Rainwater Harvesting Systems Handbook, developed by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CHMC) (Despins, 2012)[10]

| Component | Problem | Rehabilitation Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Inlets |

Pipes or fittings are damaged or displaced. |

|

| Ice is accumulating and obstructing inflow to BMP. | ||

| Cistern |

Cracks are visible or seals between joints in the structure are leaking. |

|

| Cistern has reached 40 years of age and is due for replacement. |

| |

| Overflow Outlet |

Overflow outlet pipe is obstructed by trash, debris or sediment. |

|

| Make-up water supply |

System is malfunctioning (e.g., tops up cistern water level when unnecessary or fails to top up when needed). |

|

| Pump |

Pump is not delivering water to fixtures or not providing adequate water pressure. |

|

Inspection Time Commitments and Costs[edit]

Life cycle cost estimates are based on two design variations that can be used year-round: underground concrete cistern; and indoor plastic cistern systems. For each design variation, life cycle costs can be found in the Low Impact Development (LID) Stormwater Management Practice Inspection and Maintenance Guide

Estimates of the life cycle costs of inspection and maintenance have been produced using the latest version of the LID Life Cycle Costing Tool for two design variations (underground concrete cistern; and indoor plastic cistern systems) to assist stormwater infrastructure planners, designers and asset managers with planning and preparing budgets for potential LID features.

Assumptions for the above costs and the following table below are based on the following:

- For rainwater cisterns it is assumed that no rehabilitation work will be needed to maintain acceptable storage and drainage performance over a 50 year period of operation (40 for plastic cisterns), given that pretreatment devices are in place and are being adequately maintained. The annual average maintenance cost value represents an average of routine maintenance tasks, as outlined in Table 7.28. All cost value estimates represent the NPV as the calculation takes into account average annual interest (2%) and discount (3%) rates over the evaluation time periods.

- Costs include overhead and inflation to represent contractor pricing. It was assumed the practice is part of a new development (i.e., not a retrofit), thereby excluding (de)mobilization costs unless a particular piece of equipment would not normally have been present at the site. Additionally, it was assumed that excavated soil associated with construction of the BMP would be reused elsewhere on site. Overhead costs were presumed to consist of construction management (4.5%), design (2.5%), small tools (0.5%), clean up (0.3%) and other (2.2%).

- For maintenance frequencies and requirements and the life span of each practice are based on both literature and practical experience. Life cycle and associated maintenance costs are evaluated over a 50 year timeframe, which is the typical period over which infrastructure decisions are made.

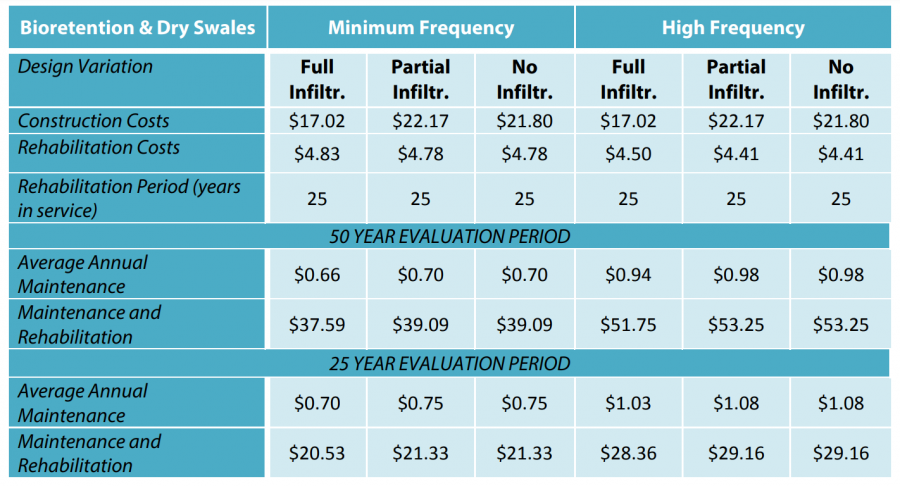

- For bioretention, it is assumed that some rehabilitation (e.g., rehabilitative maintenance) work will be needed on the filter bed surface once the BMP reaches 25 and 50 years of age in order to maintain functional drainage performance at an acceptable level. Included in the rehabilitation costs are (de)mobilization costs, as equipment would not have been present on site. Design costs were not included in the rehabilitation as it was assumed that the original LID practice design would be used to inform this work. The annual average maintenance cost does not include rehabilitation costs and therefore represents an average of routine maintenance tasks, as outlined in the Table under section, Routine Maintenance - Key Components and I&M Tasks above. All cost value estimates represent the net present value (NPV) as the calculation takes into account average annual interest (2%) and discount (3%) rates over the evaluation time periods.

- For all bioretention design variations, the CDA has been defined as a 2,000 m2 impervious pavement area plus the footprint area of a bioretention cell that is 133 m2 in size, as per design recommendations. The impervious area to pervious area ratio (I:P ratio) used to size the BMP footprint is 15:1, which is the maximum ratio recommended in the LID SWM Planning and Design Guide (CVC & TRCA, 2010)[12]. It is assumed that water drains to the cell through curb inlets spaced 6 m apart with

stone cover on the filter bed at the inlets to dissipate the energy of the flowing water.

- While orientation (i.e., cell versus swale) and choice of components (e.g., inlet/outlet structures etc.) can vary widely, design variations for bioretention practices can be broken down into three main categories. They can be designed to drain through infiltration into the underlying subsoil alone (i.e., Full Infiltration design, no sub-drain), through the combination of a sub-drain and infiltration into the underlying subsoil (i.e., Partial Infiltration design, with a sub-drain), or through a sub-drain alone (i.e., No Infiltration or “filtration only” design, with a sub-drain and impermeable liner). For Full Infiltration systems, an overflow is provided for storms up to 37 mm based on a subsoil infiltration rate of 20 mm/hour. Two standpipe wells are part of the design (one subdrain inspection/flushing port at the upstream end and one sub-surface water storage reservoir monitoring well at the downstream end). Partial Infiltration systems have a sub-surface water storage reservoir with a perforated pipe sub-drain within it. The depth of the reservoir is sized to store flow from a 25 mm rain event over the CDA based on native soil infiltration rate of 10 mm/hour. The No Infiltration system includes an impermeable liner between the base and sides of the BMP and surrounding native sub-soil, to prevent infiltration.

- Estimates of the life cycle costs of bioretention and dry swales in Canadian dollars per unit CDA ($/m2) are presented in the table below. LID Life Cycle Costing Tool allows users to select what BMP type and design variation applies, and to use the default assumptions to generate planning level cost estimates.

- Users can also input their own values relating to a site or area, design, unit costs, and inspection and maintenance task frequencies to generate customized cost estimates, specific to a certain project, context or stormwater infrastructure program.

- For all BMP design variations and maintenance scenarios, it is assumed that rehabilitation of part or all of the filter bed surface will be necessary once the BMP reaches 25 and 50 years of age to maintain acceptable surface drainage performance (e.g., surface ponding drainage time). Filter bed rehabilitation for bioretention and dry swales is assumed to typically involve the tasks outlined under section, Routine Maintenance - Key Components and I&M Tasks above.

Notes:

- Estimated life cycle costs represent NPV of associated costs in Canadian dollars per squaremetre of CDA ($/m2).

- Average annual maintenance cost estimates represent NPV of all costs incurred over the time period and do not include rehabilitation costs.

- Rehabilitation cost estimates represent NPV of all costs related to repair work assumed to occur every 25 years, including those associated with inspection and maintenance over a two (2) year establishment period for the plantings.

- Full Infiltration design life cycle costs are lower than Partial and No Infiltration designs due to the absence of a sub-drain to construct, inspect and routinely flush.

- Rehabilitation costs for Full Infiltration designs are estimated to be 26.4 to 28.4% of the original construction costs for High and Minimum Recommended Frequency maintenance program scenarios, respectively.

- Rehabilitation costs for Partial Infiltration designs are estimated to be 19.9 to 21.6% of the original construction costs for High and Minimum Recommended Frequency maintenance program scenarios, respectively.

- Rehabilitation costs for No Infiltration designs are estimated to be 20.2 to 21.9% of the original construction costs for High and Minimum Recommended Frequency maintenance program scenarios, respectively.

- Maintenance and rehabilitation costs over a 25 year time period for the Minimum Recommended maintenance scenario are estimated to be roughly equivalent to the original construction cost for Partial Infiltration and No Infiltration designs (96.2% and 97.8%, respectively), and 1.21 times the original construction cost for Full Infiltration design.

- Maintenance and rehabilitation costs over a 25 year time period for the High Frequency maintenance scenario are estimated to be 1.32 times the original construction costs for Partial Infiltration, 1.34 times for No Infiltration designs, and 1.67 times for Full Infiltration designs.

- Maintenance and rehabilitation costs over a 50 year time period for the Minimum Recommended Frequency maintenance scenario are estimated to be approximately 1.76 times the original construction cost for Partial Infiltration designs, 1.79 times the original construction cost for No Infiltration designs, and 2.21 times the original construction cost for Full Infiltration designs.

- Maintenance and rehabilitation costs over a 50 year time period for the High Frequency maintenance scenario are estimated to be approximately 2.40 times the original construction cost for Partial Infiltration designs, 2.44 times the original construction cost for No Infiltration designs, and 3.04 times the original construction cost for Full Infiltration designs.

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 TRCA. 2018. Fact Sheet - Inspection and Maintenance of Stormwater Best Management Practices: Rainwater Cisterns. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2018/02/Rainwater-Cisterns-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- ↑ Armstrong, M. D., & Csathy, T. I. 1963. Frost design practice in Canada-and discussion. Ontario Department of Highways. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/hrr/1963/33/33-008.pdf

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation. 2013. Pavement Design and Rehabilitation Manual. Second Edition. IBSN: 978-1-4435-2873-3. Published: March 2013. http://www.bv.transports.gouv.qc.ca/mono/1165561.pdf

- ↑ Armstrong, M. D., & Csathy, T. I. 1963. Frost design practice in Canada-and discussion. Ontario Department of Highways. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/hrr/1963/33/33-008.pdf

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation. 2013. Pavement Design and Rehabilitation Manual. Second Edition. IBSN: 978-1-4435-2873-3. Published: March 2013. http://www.bv.transports.gouv.qc.ca/mono/1165561.pdf

- ↑ Innovative Water Solutions. 2021. Underground Polyethylene Cisterns - An Inexpensive Option for Buried Tanks. Accessed 08 August, 2022. https://www.watercache.com/portfolio/underground-poly-tanks

- ↑ Meir, 2021. Using rainwater inside the home: What you need to know. Written by Jonathan Meier, 29 January 2021. Rain Brothers LLC. Accessed 15 August 2022. https://www.rainbrothers.com/using-rainwater-inside-the-home-what-you-need-to-know

- ↑ Rapid Plumbing Group Pty Ltd. 2022. Penrith Rainwater Services - Rainwater tanks and pumps. Accessed 15 August 2022. https://www.rapidplumbinggroup.com.au/penrith-plumber/rain-water-tank-pump-services/

- ↑ Despins. 2010. Ontario Guidelines for Residential Rainwater Harvesting Systems - Handbook. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.harvesth2o.com/adobe_files/ONTARIO_RWH_HANDBOOK_2010.pdf

- ↑ Despins. 2012. Canadian Guidelines for Residential Rainwater Harvesting Systems Handbook. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.crd.bc.ca/docs/default-source/water-pdf/cmhcrainwaterhandbook.pdf?sfvrsn=67aa96c9_2.

- ↑ Pristine Water Systems. 2017. When is the best time to clean my Rainwater Tank? Accessed 16 August 2022. https://www.pristinewatersystems.com.au/2017/02/20/best-time-to-clean-rainwater-tank/

- ↑ CVC and TRCA. 2010. Low Impact Development Stormwater Management Planning and Design Guide. Version 1.0. https://cvc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/LID-SWM-Guide-v1.0_2010_1_no-appendices.pdf

- ↑ TRCA. 2018. Inspection and Maintenance of Stormwater Best Management Practices. Bioretention - Fact Sheet. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2018/02/Bioretention-and-Dry-Swales-Fact-Sheet.pdf