Infiltration trenches

This article is about underground systems which distribute concentrated flow along a level, linear facility to promote infiltration to native soils.

For a similar structure, which differs in being designed to receive excess flow and convey it, whilst promoting infiltration to native soils, see exfiltration trenches.

Overview[edit]

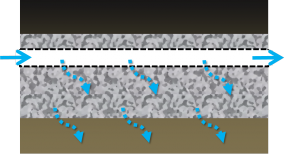

As their name suggests infiltration trenches work primarily to infiltrate and convey stormwater. They are an underground facility and are excellently suited to connecting other components in the treatment train.

Infiltration trenches are an ideal technology for:

- Installing below any type of surface or landscape

- Balancing the requirements to infiltrate excess stormwater whilst conveying excess

The fundamental components of an infiltration trench are:

- Layers of coarse aggregate to bed the pipe, store and redistribute water.

- Perforated pipe

- Geotextile

Planning considerations[edit]

Design[edit]

Sizing[edit]

Virginia up to 10' deep. [1] Infiltration: Sizing and modeling

Materials[edit]

Aggregate[edit]

This article gives recommendations for aggregate to be used to store water for infiltration. This is usually called 'clear stone' at aggregate yards.

To see an analysis of Ontario Standard Specifications for granular materials, see OPSS aggregates.

For advice on decorative surface aggregates see Stone

Gravel used for underdrains in bioretention, infiltration trenches and chambers, and exfiltration trenches should be 20 or 50 mm, uniformly-graded, clean (maximum wash loss of 0.5%), crushed angular stone that has a porosity of 0.4[2].

The clean wash to prevent rapid accumulation of fines from the aggregate particles in the base of the reservoir. The uniform grading and the angularity are important to maintain pore throats and clear voids between particles. (i.e. achieve the porosity). Porosity and permeability are directly influenced by the size, gradation and angularity of the particles [3]. See jar test for on-site verification testing protocols.

Gravel with structural requirements should also meet the following criteria:

- Minimum durability index of 35

- Maximum abrasion of 10% for 100 revolutions and maximum of 50% for 500 revolutions

Standard specifications for the gradation of aggregates are maintained by ASTM D2940

The highest porosity is found in uniformly graded aggregate, as there are no smaller particles to occupy the inter-particle pores. [3]

Higher permeability is found in larger, angular, uniformly graded aggregate. This is due to larger pore sizes and lower tortuosity. [3]

Perforated Pipe[edit]

Perforated pipes are a common component of underdrains used in bioretention, permeable pavements, infiltration trenches and exfiltration systems.

Pipes should be manufactured in conformity with the latest standards by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) or ASTM International.

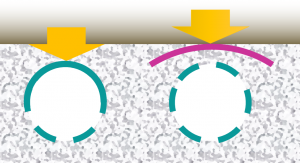

- Perforated pipes should be continuously perforated, smooth interior HDPE or PVC.

- Wherever possible pipes should be ≥200 mm internal diameter to reduce potential of freezing and to facilitate push camera inspections and cleaning with jet nozzle equipment.

- Smooth interior facilitates inspection and maintenance activities; internal corrugations can cause cameras or hydrojetting apparatus to become snagged.

- A perforated pipe with many rectangular slots has better drainage characteristics than a pipe with similar open area provided by fewer circular holes [4].

- Non-perforated pipes should be used for conveyance of stormwater to and from the facility, including overflow. It is good practice to extend the solid pipe approximately 300 mm within the reservoir or practice to reduce the potential for native soil migration into the pipe.

See also: Flow through perforated pipe

Construction[edit]

Overview[edit]

LID techniques and technologies are new to many municipalities, consulting engineers, and contractors. STEP's construction guidance aims to give practical advice, specific to LID construction, to enable practitioners to successfully construct LID practices.

Common reasons LID projects fail at the construction stage are:

- lack of detail in designs and construction documents

- Contractors can struggle to build LID facilities properly without enough detail in the contract drawings and without guidance and inspection throughout the construction process.

- lack of knowledge

- Designers often do not understand the complexities of the construction process, and contractors often don't understand the purpose of LID practices or the technologies they employ.

- lack of effective erosion and sediment control during construction

- LID practices are most vulnerable to sedimentation and clogging during their own construction or construction of adjacent lands.

- lack of planning and communication

- Poor communication protocols and the pace and extent of construction may preclude proper inspections and certifications.

Published research corroborates STEP’s experiences in the field (e.g., (DelGrosso et al., 2019 [5]); LSRCA, 2011[6]); (CWP, 2009)[7].; see the inspection and maintenance page’s overview for a more detailed discussion). Del Grosso et al., 2019 provide a helpful summary of positive considerations for LID construction: “[LID] requires more considerations during construction compared to traditional stormwater management facilities. … The proper construction of [LID] is centered around thoughtful construction sequencing, ensuring all parties involved know their responsibilities, protecting soils and media from compaction and clogging, property installing filter media and aggregate, and ensuring facilities are kept off-line until the entire drainage area is stabilized. More generally, it is important for contractors to be aware of the sensitivity of GSI and for municipalities to ensure that facilities are being inspected by qualified inspectors at critical points (Del Grosso et al., 2019, pg. 8).

Regular inspections throughout the construction process of LID practices prevent end products that are not built to the design specifications. Specifically, they ensure that:

- the LID practice has the proper layout, location, footprint, and volume;

- materials meet design specifications;

- any material substitutions and field changes to the design are verified and documented;

- the contributing drainage area is stabilized before the LID practice becomes operational;

- environmentally sensitive areas and the LID practices themselves are protected during construction; and

- inlet, outlet, pretreatment, and piped elements have the correct elevations and inverts.

Furthermore, keeping records of these inspections helps to certify the works after construction and makes for a smooth assumption process.

Construction stages and LID types[edit]

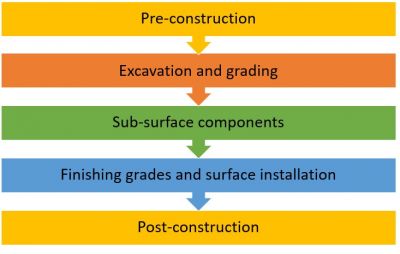

STEP divides the construction process for LID practices into five over-arching stages:

- Pre-construction

- Excavation and grading

- Sub-surface components

- Finishing grades and surface layer installation: vegetated LIDs and finishing grades and surface layer installation: permeable pavements, and

- Post-construction

Most LID practices work at the sub-surface and ground-level by routing stormwater flows from impervious surfaces into excavated or natural depressions or by allowing stormwater to pass through a pervious surface, as is the case with permeable pavements. These depressions are designed and constructed to the meet goals of the LID practice, which may be quality control, quantity control, or water balance restoration. Bioretention gardens, stormwater planters, bioswales, rain gardens, enhanced swales, exfiltration trenches, permeable pavements, infiltration systems (chambers, trenches, and soakaways), and stormwater tree trenches fall into this category.

For this reason, Stages 1-2 and 5 of the LID construction process are fundamentally similar for all sub-surface and ground-level LID types. To illustrate, STEP's recommended processes for excavation do not differ between LID practice types. Excavation procedures are the same, whether for a bioretention garden or a permeable pavement parking lot. On the other hand, stage 4 sub-tasks will vary depending on whether the LID practice's surface is vegetated or permeable pavement. Some sub-tasks in stage 3 will also vary depending on the LID type. For example, permeable pavements often require compaction of sub-surface storage layers. The following sections give a brief description of each over-arching stage, a list of sub-tasks for each stage, and links to the page dedicated to each main LID construction stage.

STEP has developed practice-specific construction inspection checklists for bioretention and dry swales, permeable pavement, enhanced swales, vegetated filter strips, underground infiltration systems (exfiltration systems, trenches, chambers, soakaways), green roofs, and rainwater harvesting.

Green roofs and rainwater harvesting systems have specific construction sequences and requirements that differ from the main sequence described above. STEP has developed guidance for green roof construction; guidance on installing rainwater harvesting practices is forthcoming. When installing these BMP types, always consult the product manufacturer's guidance.

Pre-construction[edit]

Pre-construction activities set the stage for the successful construction of an LID practice. The pre-construction page gives guidance on:

- design verification and site walk-through

- LID construction notes

- tendering and contract

- communication, inspection plan, and utilities coordination

- erosion and sediment control measures

- mobilization, access, staging, and perimeter controls

Excavation and grading[edit]

Excavation and grading are necessary for installing LID practices with sub-surface components, re-grading land to hold more water, and re-routing overland flow routes into an LID practice. The excavation and grading page gives guidance on:

- clearing and grubbing

- excavation and rough grade

- sub-grade

- final excavated grade and verification

Sub-surface components[edit]

Most LID practices use a combination of sub-surface features such as gravel storage reservoirs, liners, underdrains, monitoring wells, and other components to meet their design objectives. The construction process for sub-surface components works from the ground up. While some LID practices include all the sub-surface components listed below, most designs will not include one or more of these layers or components. Permeable pavements can have different construction requirements at this stage, mostly regarding compaction of sub-surface layers. Installing infiltration chambers also requires guidance specific to that LID type. Stormwater Tree Trenches, which consist of subsurface trenches filled with modular structures and growing medium, or structurally engineered soil medium to supporting an overlying pavements, also require advice specific to them.

The sub-surface components page gives guidance on:

- geotextile

- underdrain

- impermeable liner

- overflow

- monitoring wells

- storage reservoir

- sub-base reservoir (permeable pavements)

- base course (permeable pavements)

- infiltration chambers

- choker layer

- curbing and curb cuts

- pretreatment and inlets

Finishing grades and surface layer installation[edit]

This construction stage differs between LID practice type. The finishing grades and surface layer installation: vegetated LIDs page has guidance for vegetated LIDs, and the finishing grades and surface layer installation: permeable pavements page has guidance for and non-vegetated LIDs. In many cases the surface of infiltration systems will be traditional asphalt, concrete, or pavers; STEP does not provide guidance on installing non-permeable surfaces.

| LID practices with vegetated surfaces | Permeable pavements |

|---|---|

| soil media installation and soil amendments | bedding layer |

| finish grading | placement and finishing |

| large stone and riprap | paver installation |

| plant verification and installation | tamping |

| mulch placement | joint cutting |

| stabilizing contributing drainage area and planting adjacent vegetation | joint aggregate |

| -- | curbing |

| -- | stabilizing contributing drainage area |

Post-construction[edit]

Post-construction tasks ensure that the LID practice was built to specs and that any outstanding issues with it are resolved before assumption. The post-construction page give guidance on:

- Addressing deficiencies

- Final certification

References[edit]

Gallery[edit]

View of infiltration trench in U.S. Photo credit: Moreau1

- ↑ Viriginia Deprtmant of Transport. (2010). VDOT BMP Design Manual of Practice. Retrieved March 15, 2018, from http://www.virginiadot.org/business/resources/LocDes/BMP_Design-Manual/Chapter_8_Infiltration_Trench.pdf

- ↑ Porosity of Structural Backfill, Tech Sheet #1, Stormtech, Nov 2012, http://www.stormtech.com/download_files/pdf/techsheet1.pdf accessed 16 October 2017

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Judge, Aaron, "Measurement of the Hydraulic Conductivity of Gravels Using a Laboratory Permeameter and Silty Sands Using Field Testing with Observation Wells" (2013). Dissertations. 746. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/746

- ↑ Hazenberg, G., and U. S. Panu (1991), Theoretical analysis of flow rate into perforated drain tubes, Water Resour. Res., 27(7), 1411–1418, doi:10.1029/91WR00779.

- ↑ Delgrosso, Z.L., Clayton, C.H., Dymond, R.L. 2019 Identifying Key Factors for Implementation and Maintenance of Green Stormwater Infrastruture. Journal of Sustainable Water in the Built Environment. 5 (3): 05019002. https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/JSWBAY.0000878

- ↑ Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA). 2011. Stormwater Pond Maintenance and Anoxic Conditions Investigation. Final Report. Newmarket, ON. https://sustainabletechnologies.ca/app/uploads/2015/01/LSRCA-Stormwater-Maintenance-and-Anoxic-Conditions-2011.pdf

- ↑ Centre for Watershed Protection. 2009. Technical Report Stormwater BMPs in Virginia’s James River Basin: An Assessment of Field Conditions & Programs (part of the Extreme BMP Makeover project). Prepared by David Hirschman, Laurel Woodworth, and Sadie Drescher Center for Watershed Protection, Inc. Final Draft. June 2009. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/channel_files/19219/cwp_james_river_tech_report_final_draft_062509.pdf.pdf